A couple of years ago, a very dear friend looked me in the eyes and called me a “Startup Snob”. It stung, but I had to admit he had a point. I’ve been involved in the startup scene since as early as 2001, when I became a tech journalist covering the exciting world of startups, interviewing CEOs and product leaders about their innovations. By 2007, age 27, I joined David S. Rose’s company Gust (then called AngelSoft) in NYC, and became a Product Manager. It was the first crowdfunding platform for Angels, VCs, and entrepreneurs, and I got to talk to founders daily, support their funding journeys with product features, and sit on multiple investor pitches. In 2009, I became the Director of Product at SetJam, a smart TV startup we eventually sold to Motorola in 2012, just as Motorola itself was being itself acquired by Google.

So yes, I was one of those people who believed that the heroic and hard period in a startup’s life are those scruffy early years. Getting those first 100 users. Going from Zero to One.

It was only in the past few years, after I founded Remake Labs and focused our offering on strategic GV-style Design Sprints, that I began to challenge some of my assumptions. We’ve now run multiple sprints with rapidly scaling startups in the 500-600 employee range, and have found everyone there to be remarkably bright, talented, and hardworking, and the environment fun and energizing. Still – rapid growth has presented unique and non-trivial challenges.

As priorities, products, and distractions multiply due to rapid growth — keeping the product innovation pipeline flowing is a massive undertaking, especially with uneven distribution of experience, knowledge, and talent.

“As far as I could tell, the way most large companies started new products was just chaos… but I thought there could be something really great there.”

Jake Knapp, Sprint creator

It brings up not only tactical but also semi-philosophical questions, like: Can creativity scale? Can it be standardized? How can cross-functional teams work together well reliably across multiple projects? How can we disseminate and embed best practices at scale? Etc.

Interestingly – the Sprint process which I love so much, was originally developed at Google, as an attempt to solve just such scaling challenges. When I interviewed Sprint creator Jake Knapp in 2020 he emphasized this. There were perhaps 50 product designers at Google at the time, and they needed to support a much larger organization composed mostly of engineers. The design sprint allowed the designers to go where they were most needed, and to condense as much value into a single week as they could – giving teams a wonderful starting point to build on.

So here’s what I think sprint-running companies have taught me, and can teach scaling startups about scaling innovation:

1. The Important Must Be Defended from the Urgent

As companies and teams grow rapidly, the amount of noise and work generated from within the company increases expontentially. This can be an exciting thing – the team has it’s own culture, a mini-society with its own rituals, traditions, a shared language — and lots of cool people to meet and learn from. Cross-functional taskforces multiply, professional Guilds may created to support different roles and share information across teams. So far so good.

But when you’re constantly bombarded with requests from different teams and projects, it’s tough to find time to focus on the important things—the things that will move your product forward. Time for deep focus, strategic thinking, and creative solutions shrinks – which can be both frustrating and counter-productive.

That’s where Google’s Design Sprint process comes in. By setting aside all other priorities for a week and focusing on one big challenge with a cross-functional team, even busy, overwhelmed Product Managers get to set and defend time for important product thinking and discovery.

Time for deep focus, strategic thinking, and creative solutions shrinks – which can be both frustrating and counter-productive.

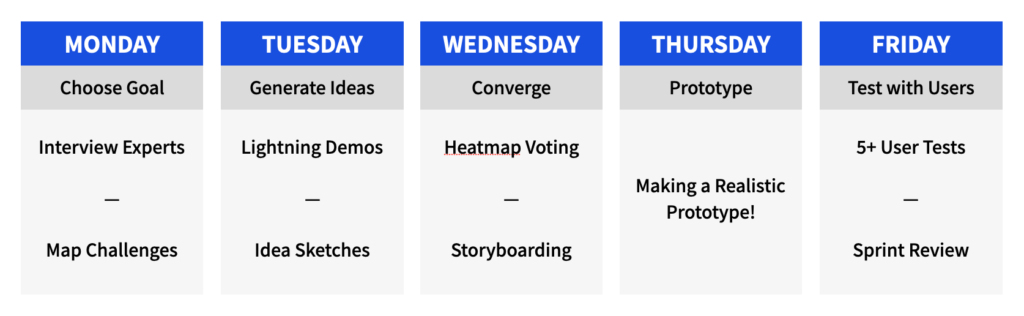

The Sprint forces you to focus on the most important thing you can do for your product right now and blocks out everything else. Here’s how it works: First, you identify the problem you want to solve. This can be anything from “We need to improve our onboarding conversion rates” to “We need to adapt the product to a new type of user.” Then, you follow a step by step process that lasts 5-days, and takes you from research and discovery, through inspiration and ideation, and finally to decision, convergence, prototyping, and testing with actual users.

The Design Sprint process provides a fun, collaborative, and very high quality time-frame to focus on the important things and block out the noise of competing requests. By taking the time to identify the problem you want to solve, then developing and testing potential solutions, you can be confident that you’re working on the right thing — the thing that will actually move your product forward.

2. Context Switching and Team Fragmentation Can Grind Projects to a Halt

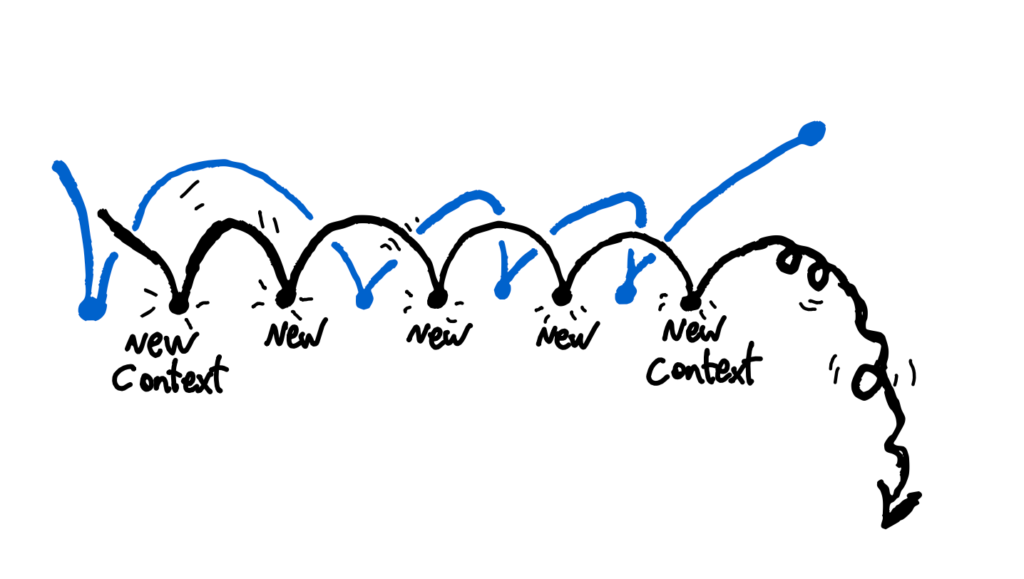

As your cross-functional leadership team members are increasingly forced to juggle multiple priorities and projects, and are rarely available at the same time, the exchange of information and the rate and quality of decision-making goes down hill. In addition, team members lose a significant chunk of every day recovering from context switching, or having to remind themselvse of the complexities and priorities of a project they set aside to focus on the latest fire.

Google’s Design Sprints is the perfect solution to this problem. By bringing all decision makers and experts together for a distraction-free, focused week of discovery, design, and validation, fragmentation and context switching is eliminated. Distractions are held at bay, and immersion in the challenges and complexities of the project gets deeper and deeper for all involved.

Indeed, many have found that Design Sprints speed up time to a new product solution from months to days, creating better outcomes in 5 days that may otherwise happen in a whole quarter!

Sprints also liberate teams to work more effectively after their done. By providing better clarity, alignment between cross-functional teams, and a shared vision – they can speed up development and prevent scope-creep for many months following.

3. Innovation Can Become Predictable

To many, creativity sounds like a mystical, squishy subject that cannot be defined, encoded, or predicted. This isn’t what some of the leading creativity and innovation experts say though. In my conversation with author and creativity guru Natalie Nixon, she emphasize that creativity is a robust and methodical process balancing wonder and rigor. Design Thinking experts teach us that finding creative solutions often follow a set and predictable path from emphathy to definition, ideation, divergence and convergence, prototyping and testing.

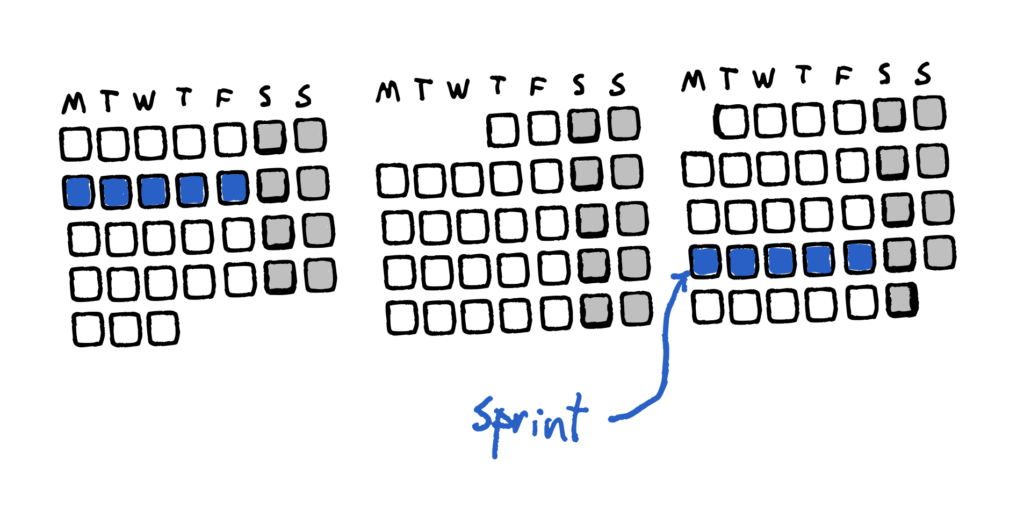

One of the truly magical aspects of the sprint is that it condenses these stages of creativity and problem solving into just 5-days, still giving us enough time to immerse, emphathize, ideate, and prototype — but also introducing another crucial element: predictability.

Very few creative processes lend themselves so naturally to scheduling. By scheduling, let’s say, a sprint each quarter, we can be quite sure that we’ll have a prototype on a certain date. It is then possible to pencil in sufficient time for corrections and iteration, and know when development will start.

In addition, sprints bring predictability to staffing, resources, and the amount of projects that can be reasonably be advanced in a given period of time. By being so condenced themselves, they represent a reasonable estimate of the company’s maximum innovation bandwidth given a certain number of team members and time.

This is predictability is priceless when it comes to planning and ritualizing innovation, and creating a predictable innovation pipeline.

4. Creativity & Hierarchy Are Often at Odds

We often have to remind our clients to relax hierarchies when approaching a creative problem-solving task. The reason why everybody is asked to participate is precisely beause the correct answer is unknown. Not by any team member, nor by the leadership. Sprints by their nature try to make inroads into the unknown and ambiguous, and help us develop greater clarity and confidence, and better intuitions.

The Sprint process, especially when an outside facilitator is brought in, allows leaders to put down the burdens of leadership and simply participate, think, ideate, sketch, and be creative with the rest of the team. Because of the sprint’s tight structure and room for experimentation, they don’t need to be perfect, have all the answers, or worry about managing the team’s feelings. They also are free not to manage or worry about the process, and focus their attention on the challenge at hand.

Not having any emotional attachments, biases, or affiliation with internal politics — an external facilitator is more readily accepted by all parties, and the process thus benefits from multiple points of view and forms of expertise, without getting bogged down in endless discussions or power struggles.

Other participants as well are free to express themselves, knowing that their ideas will be heard and valued, and not worring about getting judged for having an alternative view to that of the leadership.

In the end, we often see that the best solutions emerge from introverts, people low in the hierarchy who are closest to the problem, or people who have no expertise in product design but are deeply immersed in a particular aspect of the challnge. (For example sales reps, customer support, marketing professionals, engineers.)

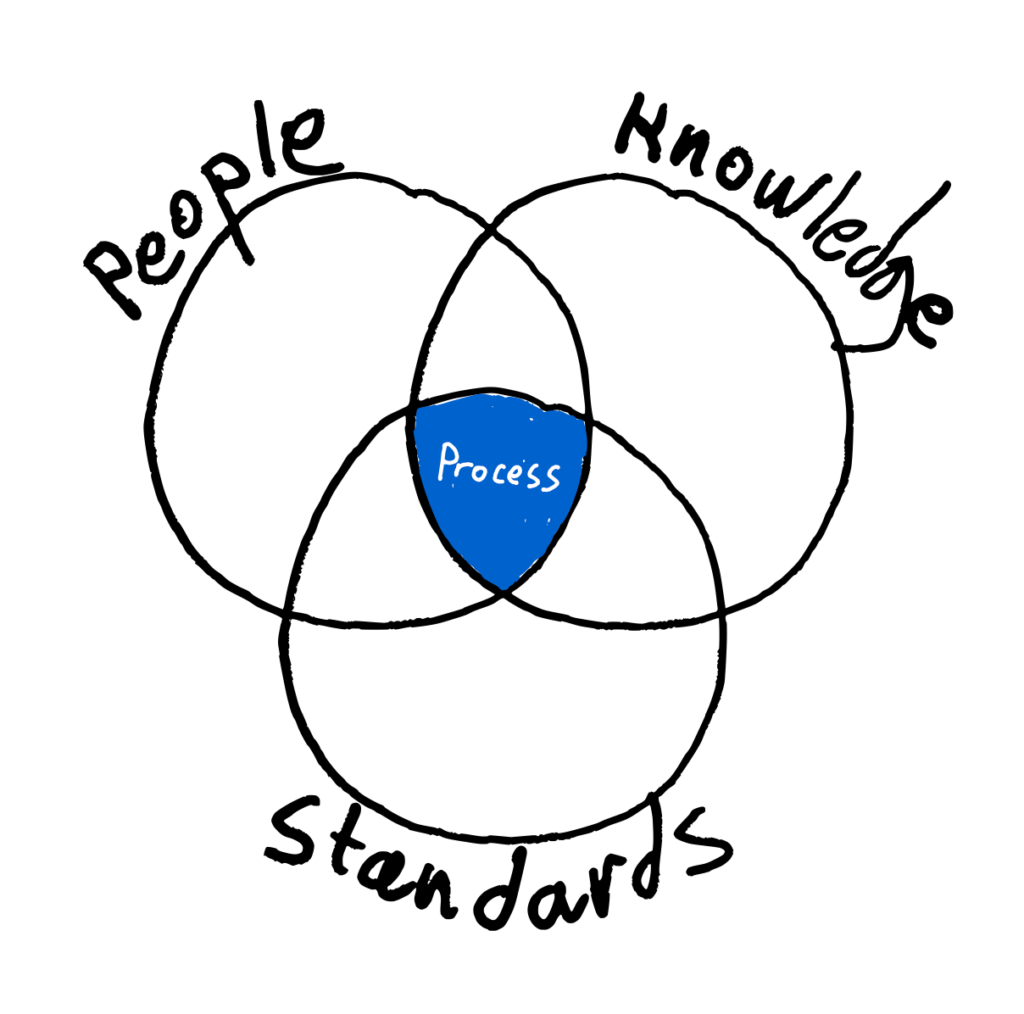

5. Great People Are NOT Enough

Product innovation and design is just as much about a great process than about great people. When growing very rapidly, it’s hard to keep standards high, keep teams inter-operational, and consolidating and codifying the best learnings from across task-forces. As a result, some teams always perform considerably better than others.

Sprints are kind of like algorithms, but for groups of people instead of computers.

— Jake Knapp

The difference often results from extremely hard to detect differences in team culture, personalities, psychological safety, and shared buy-in related to methods.

The Sprint process does something remarkable, that many fail to properly appreciate: by turning best practices into precise, step-by-step instructions that work well together, the Sprint is like a computer program or an algorithm – which can be improved, revised, and perfected regardless of the people running it.

Jake called my attention to this aspect: “Sprints are kind of like algorithms,” I heard him say once, “but for groups of people instead of a computer.”

What this means in practice is that companies can encode and incorporate best practices and best learnings from across the company and the world, and encode them in their internal sprint structure. This allows great people not only to be consistently great themselves, but also to make the people around them great by enforcing best practices as a “ritualized”, time-boxed workshop where skipping steps and ignoring guidelines is all that much harder.

The result promises to equalize outcomes across teams, upskill low performing teams, and amplify the efforts and innovation of best performing teams.

6. Magic Happens When Cross-Functional is… Functional

Bringing cross-functional teams together around a challenge is not new. It’s the core idea around any taskforce. But there’s a difference between working side by side and truly communicating and benefitting from cross-functional opinions, expertise, and points of view.

Cross-functional teams that work beautifully together can solve complex problems in a way that no single-speciality can. They can take into account many different concerns and priorities simultaneously, and get to the simplicity on the other side of complexity more readily.

But achieving that level of cross-functional integration is a great challenge at scale. Particularly with strategic and multi-disciplinary challenges.

Sprints do a remarkable job of putting cross-functional teams on the same footing, providing them with the same three-dimensional information, eliciting feedback an ideas at every step of the creative process, and exploring multiple options before converging on the best solutions.

As a result — they effectively integrate front and back office, strategy and tactics, customer support, sales, marketing, tech, and design. Once everyone feels included and has their ideas taken seriously, the result is inevitably greater alignment and momentum around a shared new vision.

Doing this at scale is nothing short of magic. Doing it consistently is a strategic asset. Design sprint help companies do both by creating an effective protocol for exploring, deciding, and converging around the best solution.

7. Total Immersion: Onboarding a New Team Quickly.

Total immersion is not just a great way to learn a new language. It’s also a great way to onboard a new product team.

Working with startups of all sizes, one thing has proved repeatedly true: there is simply no better way of onboarding a team to a new project than a Design Sprint. By listening to experts, defining key challenges, looking at the competition, ideating, prototyping, and testing — each team member, whether brand new or experienced, gets a well-rounded understanding of the challenge without having to go through intense training or handholding.

At the end of the week – everyone is an expert, having spent 40 hours specializing in the challenge in all its facets.

That’s why an emerging practice for scaling startups is to run a Design Sprint soon after assembling the team to lead this new project. Starting together on day one creates the right culture, the right respect for complexity, and irons out any misunderstandings or misalignments right off the bat – enabling teams to highly perform from day one.

—

I hope you see now why both rapidly growing startups and large corporates have begun to implement Design Sprints in some form as part of their repeatable innovation pipeline. At Remake Labs, we serve as external partners to companies looking to iterate on this approach by facilitating sprints, offering internal team trainings, and customizing the sprint process to include company-specific tools and learnings.