Late last year we had the honor and pleasure to join researchers from Cambridge University’s Center for the Study of Existential Risk (CSER) and researchers from Oxford University’s Future of Humanity Institute (FHI) in leading a Design Sprint workshop on an interesting problem: how to help decision makers in tech companies, governments, militaries, and NGOs better understand the onslaught of new Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning technologies, the new capabilities they provide to various players, and the effects they might have on geopolitics, business, defense strategy, and work in the 21st century.

Background on the Problem

The Importance of Alignment

In recent years, the development of artificial intelligence technologies have reached a scope and a velocity that concern experts and laymen alike. In 2017, for instance, DeepMind’s AlphaZero displayed a remarkable ability to self-teach the games of Go, Chess, and Shogi through self-reinforcing play, which allowed it to achieve super-human levels within a day. In 2018, A language processing AI from Alibaba beat top humans at a reading and comprehension test at Stanford University. The same year, Google announced Duplex, an AI assistant which can book appointments over the phone, without the service providers ever realizing the caller is non-human.

The concern seems to be shared by many industry leaders. In January 2015, an Open Letter on AI published by the Future of Life Institute at MIT made headlines around the world. Here’s a quote:

“The adoption of probabilistic and decision-theoretic representations and statistical learning methods has led to a large degree of integration and cross-fertilization among AI, machine learning, statistics, control theory, neuroscience, and other fields… Because of the great potential of AI, it is important to research how to reap its benefits while avoiding potential pitfalls… We recommend expanded research aimed at ensuring that increasingly capable AI systems are robust and beneficial: our AI systems must do what we want them to do.”

Some of the letter’s more than 8,000+ signatories are Steve Wozniak, Elon Musk, and the late Stephen Hawking, as well as the co-founders of AI leaders DeepMind and Vicarious, Google’s director of research Peter Norvig, Professor Stuart J. Russell of the University of California Berkeley, and many other AI experts, robot makers, programmers, and philosophers, among them numerous leading academics from Cambridge, Oxford, Stanford, Harvard, and MIT.

Preceding the letter by only a few months, was Oxford’s Professor Nick Bostrom’s book Superintelligence. Bostrom, who founded The Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford University, attempted to provide a systematic and methodical overview of the risks of and possible approaches to the arrival of super-human machine intelligence.

The problem of appropriate use and guidance of AI can broadly be referred to as “The Alignment Problem”. Simply put, alignment becomes important because AI is a technology that by definition lacks steering or controls. AI algorithms are “trained” and then empowered to make their own decisions in real-world situations. Often – millions or billions of decisions in a single day. There are many risks, both near term and long term, that are associated with this inherent autonomy.

In their white paper about Ethically Aligned Design, the IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) lists some of the key challenges of alignmnent, including some hefty ethical dilemmas:

“- How can we ensure that AI/AS do not infringe human rights? (Framing the Principle of Human Rights)

– How can we assure that AI/AS are accountable? (Framing the Principle of Responsibility)

…

– AIS can have built-in data or algorithmic biases that disadvantage members of certain groups.

– As AI systems become more capable— as measured by the ability to optimize more complex objective functions with greater autonomy across a wider variety of domains—unanticipated or unintended behavior becomes increasingly dangerous.

…

– AWS are by default amenable to covert and non-attributable use.

– Exclusion of human oversight from the battlespace can too easily lead to inadvertent violation of human rights and inadvertent escalation of tensions.

– How can AI systems be designed to guarantee legal accountability for harms caused by these systems?”

This questions are not theoretical. They are key strategic questions that should drive government policy, military strategy, business strategy, and social discourse over the coming decades.

Another obvious concern tangled with the growth of AI competence has to do with the economic value of humans and human work, and the ways in which human talent is gradually, and sometimes not so gradually, being replaced by machines. While it’s important not to fall into fear mongering, the scope of the problem should be understated.

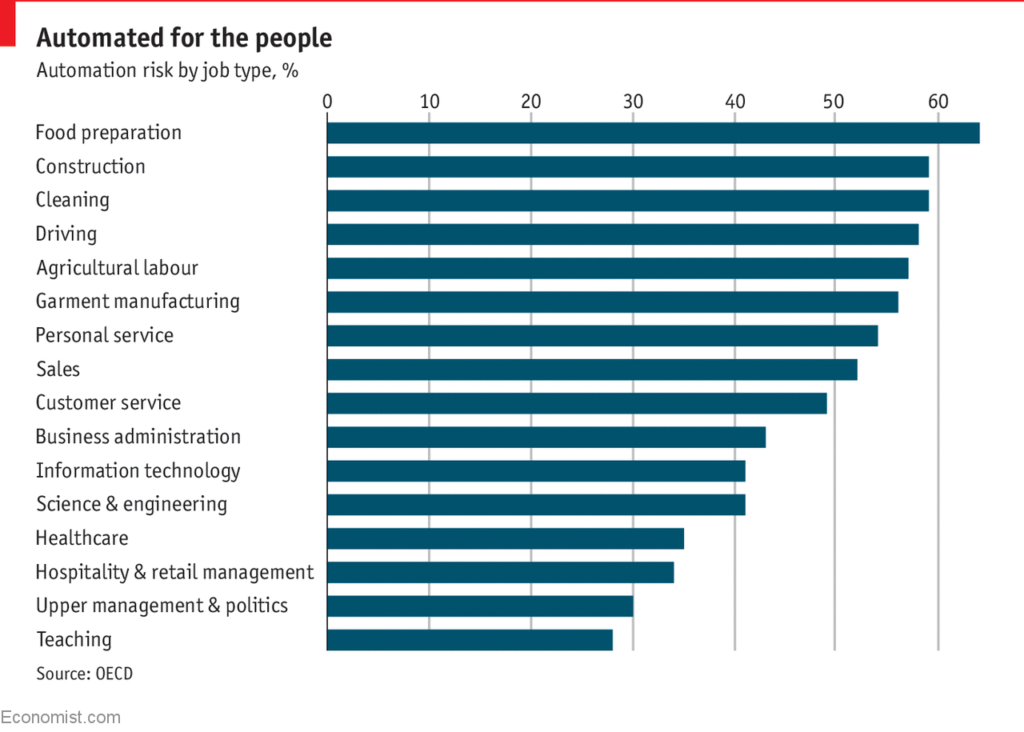

A recent OECD study found that nearly 50% of all jobs are vulnerable, with the top categories being: Food preparation, construction, cleaning, agricultural labor, garment manufacturing, personal services, sales, customer service, business administration, and even science & engineering, upper management, and politics.

Automated risk by job type, a summary of the OECD data in “A study finds nearly half of jobs are vulnerable to automation” in The Economist, April 24th 2018, retrievable from – https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2018/04/24/a-study-finds-nearly-half-of-jobs-are-vulnerable-to-automation

How will human survive in a world where many of their traditional jobs aren’t valued? This is a genuine and frightening question to ponder. Writes Max Tegmark in his book Life 3.0:

“If AI keeps improving, automating ever more jobs, what will happen? Many people are job optimists, arguing that the automated jobs will be replaced by new ones that are even better. After all, that’s what’s always happened before, ever since Luddites worried about technological unemployment during the Industrial Revolution.

Others, however, are job pessimists and argue that this time is different, and that an ever-larger number of people will become not only unemployed, but unemployable. The job pessimists argue that the free market sets salaries based on supply and demand, and that a growing supply of cheap machine labor will eventually depress human salaries far below the cost of living.”

The thought is frightening, and it seems that the answer lies not in correctly programming the mind of AI itself, but in building a societal and political system which values each human being as an end in itself, rather than as a necessary means to another end.

5-Day Design Sprint at Oxford University

So what can one do about all of these risks?

In the past couple of years, Dr. Shahar Avin from CSER at Cambridge has been researching AI risk, and developing a strategic role-playing game based on the rich US Army’s wargame tradition as a way of exploring future scenarios and teaching decision makers about various risks. Shahar has been running them in person with AI researchers, strategists, and other groups. (In fact, we met on one such occasion, at the Augmented Intelligence Summit in California.) But the team wanted to design a game that could be shipped and played without Shahar, or an equally well-versed game master, and which could produce insights for both researchers and decision makers during a relatively short 2-hour game.

So we flew to the UK, took a train to Oxford, and spent 5 days amongst some of the smarted researchers dealing with these topics.

Monday: Defining the Sprint Goal

Expert Interviews, and “How Might We”s

Expert interviews session at FHI’s Petrov conference room, named after Stanislav Yevgrafovich Petrov. All the conference rooms at FHI are named after people who actually saved the world.

The first day of the sprint, as is usually the case, was a full day of interviews. Unlike most sprints though, this sprint experts were mostly Phds and Phd Students from Oxford and Cambridge, with expertise in in AI risk, AI governance and policy, Machine Learning, and more. By the end of the interview part of the day, we’ve collected hundreds of HMW (How Might We) notes.

This is our first sprint where we had to be careful not to erase the equations on the whiteboard, because they could one day save humanity.

We felt a bit overwhelmed, but at the end of the voting exercise we had a clear top 5 selection, and a massive challenge ahead of us:

1. How might we ensure that we are taken seriously by tech people and AI researchers?

2. How might we speed up the rate of the game, so that we can get a meaningful game inside of 2 hours?

3. How might we ensure that the game can be adapted for various needs (research, education) and scenarios (near future, far future?)

4. How might we more accurately reflect various real-world actors’ motivations, beliefs, capabilities, restrictions, incentives, resources, etc in the game?

5. How might we design a game that is insightful but not too scary or pessimistic?

Long Term Goal, and Key Questions

We then brainstormed and ultimately selected a long term goal for the project:

[ Our Long Term Goal candidates.]

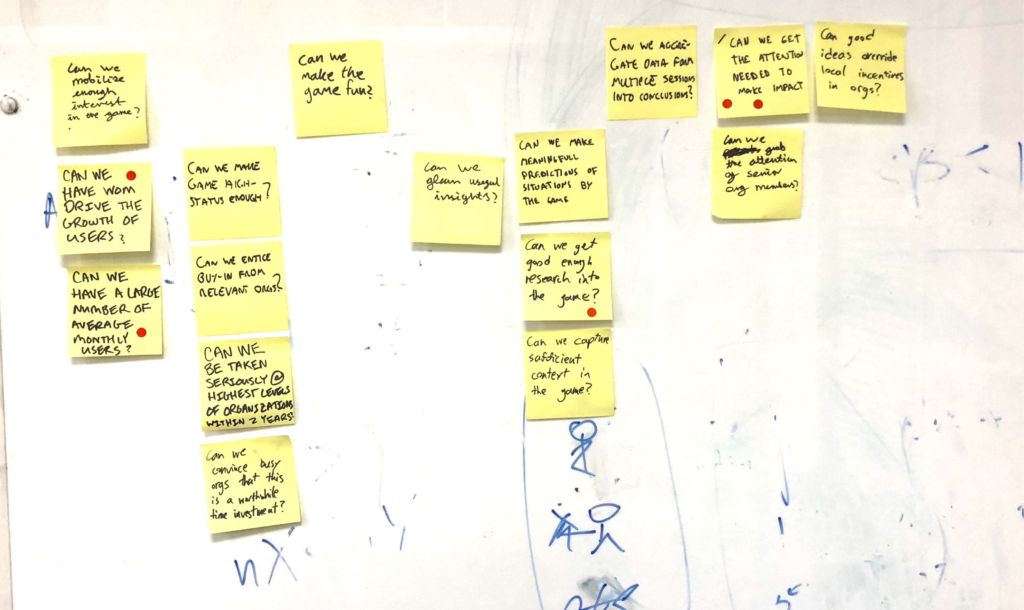

Now it was time to figure out the 3 key sprint questions that we’ll be testing in the sprint. These questions are design challenges that we need to get right during the Sprint, if the Long Term Goal is to be accomplished. We each wrote a few of these as “Can We” questions and voted on them to select the top 3.

Here’s what we selected:

1. Can we be taken seriously by decision makers, as an RPG?

2. Can we reliably generate insights in sufficient quality and quantity per game?

3. Can we get players to trust the game and its lessons?

Makes sense, right? In order for insights from the game to be used by decision makers, the game has to be taken serious, generate enough insights, and have those insights be trusted enough to act on. This is the challenge we had to solve over these 5 days.

The Sprint Map

Finally – we focused on the User Journey map. We started with 3 different “user types” – the Players, the Game Master or GM, and the System. (Originally the system was represented by Shahar himself, but now it will be represented by the kit). We then drew a flow that included:

- Finding a venue

- Organizing logistics

- Doing an introduction to the game

- Preparing a scenario and characters

- Developing familiarity with characters

- Setting the scene

- Playing the 1st turn (We went into the turn structure a bit)

- Repeating turns until the world ends (in either catastrophe or utopia).

- The GM reveals hidden/secret states of the world

- Reflection and Review (Debrief)

- Collection of Game Feedback

As you can see – instead of focusing on just one key area, we decided to focus on 5 key moments in the journey that define the overall experience: GM Setup, Player Setup, Character Setup and Assignment, Turn Structure, and the Final Debrief. Thus, we had a clear goal and a massive challenge ahead.

Tuesday: Inspiration and Divergent Thinking

We started Tuesday morning getting kicked out of the nice big conference room and having to re-settle at a much smaller one. Since the sticky notes and map representing the “group brain” are so important, we spent the first half hour migrating everything to the smaller room. (It was covered in yellow paper by the end.)

We then started with our usual Sprint Tuesday routine, which included:

Lightning Demos

We started by lining up our demos: each person bringing examples of relevant products they liked, other strategic games we could learn from, and any other relevant example of similar problems being solved by someone else. We all came prepared, but I gave the team 1 hour to research and line up all their demos.

We then proceeded to give short 3-minute presentations of each relevant solution. I won’t go into full detail here, but here’s just a sample of the type of demos we’ve looked at: Naval Academy war-games, the Sim City game, Sid Meyer’s Civilization , the Eclipse RPG system, the ArXive repository for AI papers – and dozens more.

At the end of this exercises, we were pumped with ideas and inspiration. So we broke for lunch, to let the subconscious start working it’s magic!

Sketching Ideas

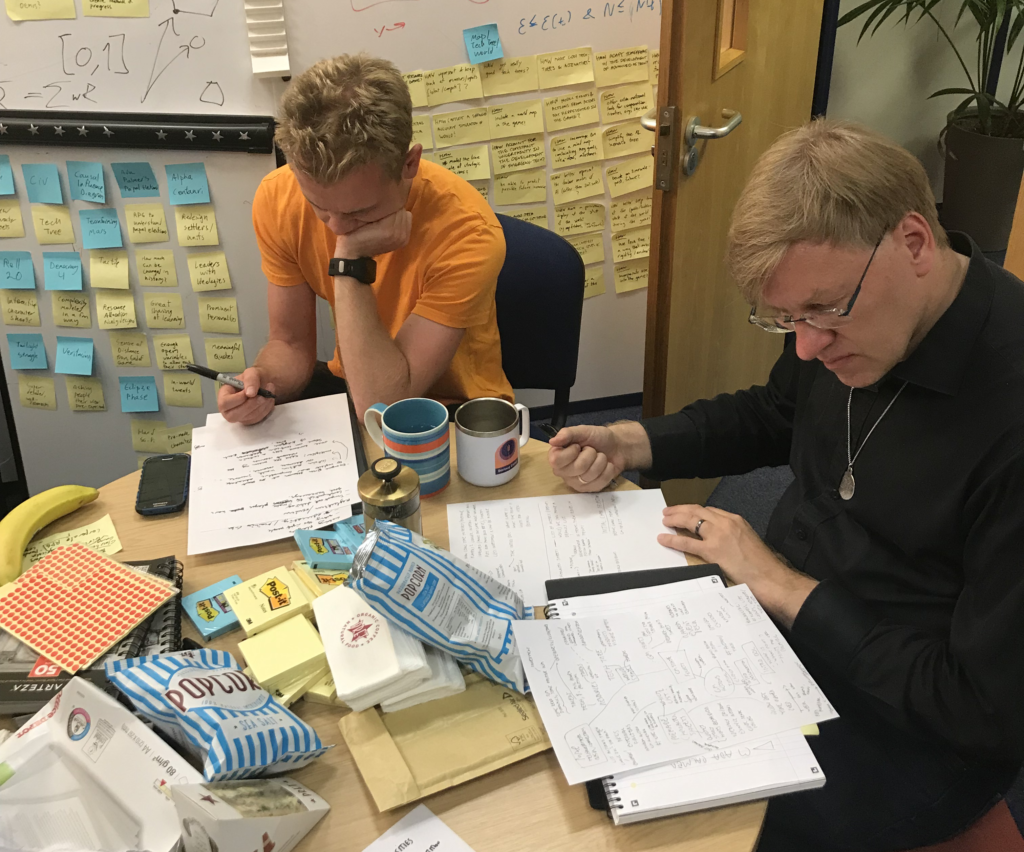

Coming back from lunch, and for the rest of Tuesday, we were busy sketching out our ideas, following the Sprint’s 4-step process. It was a pleasure sitting with such smart people

At the end of the day, I have collected everyone’s sketches, and verified that they were readable and properly annotated for the next day, where we would be discussing and voting on them.

Wednesday: Converging on a Solution

As Sprint members were coming in and making their first coffee, we hung up everyone’s sketches on the wall — forming a gallery of everyones ideas and solutions.

The day began with everyone perusing everyone’s sketches in silence, and using red sticky dots to register their interest and enthusiasm for different aspects of everyone’s ideas. We then had a structured discussion of each idea, making sure that the whole group understood what was being proposed and that nothing was missed.

Some of the most exciting ideas were:

- The introduction of cards containing key technologies, products, and events.

- The introduction of a World Chaos meter, to summarize how well humanity is handling new AI technologies.

- The introduction of neatly boxed out character sheets for key world players including the heads of AI labs, world leaders, tech CEOs.

- The introduction of a world map to orient the players.

- And many more…

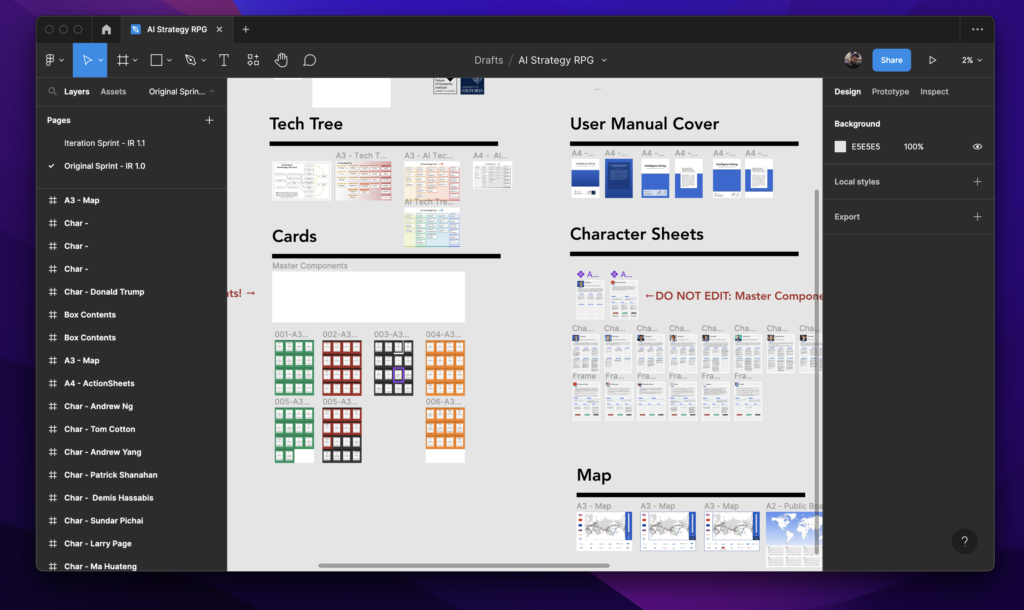

Shahar, who is the official Decider, then locked in the decision of which aspects of people’s ideas were going to make it in. The rest of the day was dedicated to sketching and outlining the key assets we were going to need. These included:

- A Box

- A Player’s Guide

- A Series of Character Sheets

- A Technology Tree

- A Deck of Technology and Event Cards

- An Action Sheet

- A Map with a World-Chaos Meter

We’ve used the best aspects of everyone sketches to start this outline, knowing that the next day — prototyping day — was going to be especially challenging.

Wednesday Night: Hobbit Dinner at The Eagle and Child

Since we were already in Oxford, we stopped for dinner at The Eagle and Child, which is a legendary pub where famous for being the place where J. R. R. Tolkein and C. S. Lewis used to drink and chat about writing! If you’re a Hobbit or Lord of the Rings fan like we are, you’ll appreciate me saying that the place totally looks and feels like Bag End. Plus the savory pies were delicious!

Thursday: Prototyping Day!

We were a large group, and that was lucky because we needed each person. Myself and Shahar (That’s Dr. Shahar Avin from Cambridge to you) worked on making the AI Tech tree readable and understandable to non-experts. Then Ross Gruetzemacher (Phd Candidate, Auburn) and Dr. Shahar Avin holed up in a room and worked on composing the User Manual from scratch.

We were lucky to be using Figma, with its real-time collaboration options, because James Fox (Phd student, Oxford) was working on creating research-based Character Sheets, while Dr. Anders Sandberg (Oxford, FHI) was working with our intern Ariel Kogan on creating the ~150 game cards for the game. In the meantime, myself in Oxford and Shay Shafranek joining from NYC were working on designing these assets, and making them available to the team for content-creation.

This included a MacBook Pro box which we converted to an impressive looking game box, and all the game assets – which had to be printed. Shahar and I made it to the print shop just before closing time! and printed all the assets on high quality paper for the next day’s play-tests.

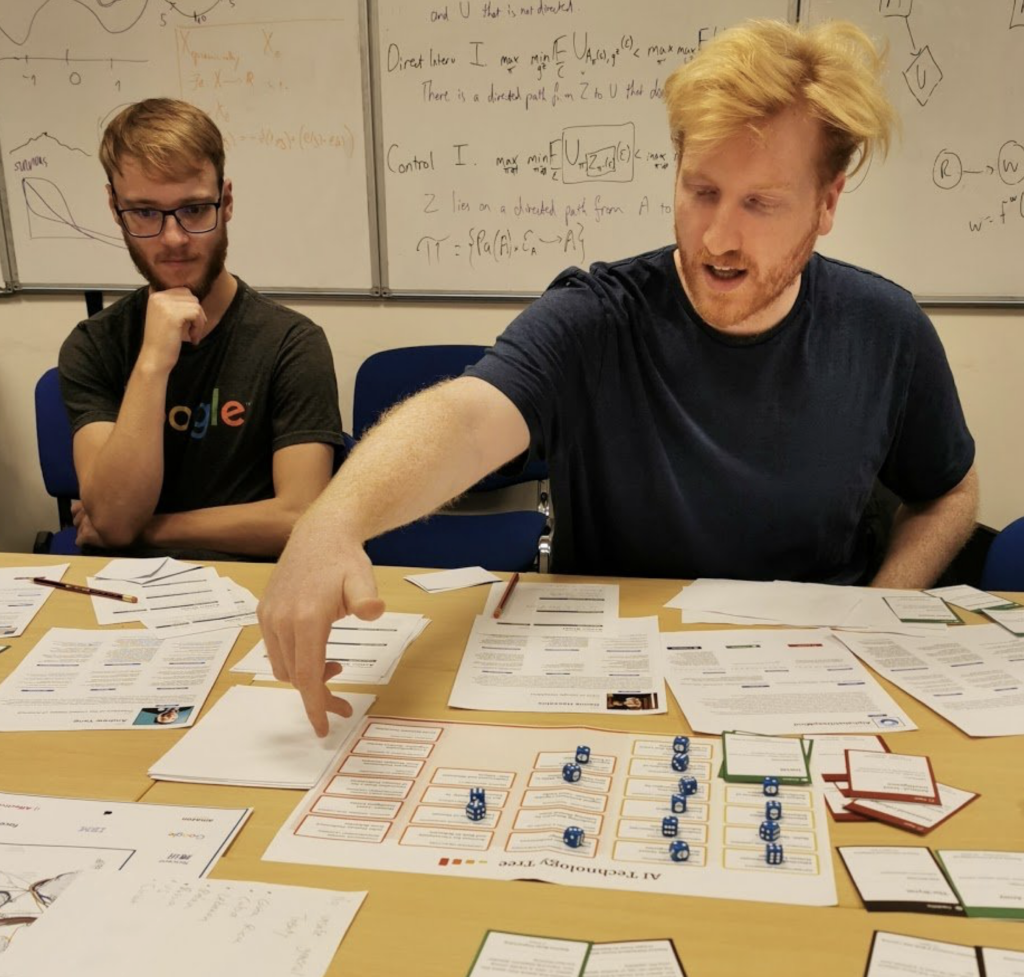

Friday: Play-testing the Game

Because this project is a strategic game, and one played in a group at that, we decided to conduct two separate 2-hour playtest sessions at Oxford. The first playtest took place in Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute, with researchers familiar with AI capabilities and the risks associated with it. For the second playtest, we invited a group of Political Science and Humanities students from Oxford: intelligent and sophisticated, sure — but not as technical. These students would better represent the political and business leaders we are seeking to educate.

We recorded the sessions and also had observers take notes, to make sure we extract the most useful information on what works and what doesn’t work. Both games went surprisingly well – with players taking the games seriously and learning a lot about the risks and problems in the process. There were also real surprises in each game, which highlighted possible risks or dynamics to think about. In one game, the team that played the Chinese government managed to sneak a key vulnerability into a key international AI project, which allowed it to subtly manipulate events in its favor. In another — the team that played the Google corporate family avoided US government oversight by suddenly announcing that it is moving its headquarters and AI labs to another country.

Summary and Conclusions

After the sprint – we held a conference call to summarize our impressions and notes, and continued to outline priorities for future development. We’ve also made some immediate adjustments that allowed us to continue to play and learn.

Since then – the game moved on forward full throttle. It’s been played at dozens of AI-related conferences and workshops around the world, and at a handful strategic conferences — including one with the British Ministry of Defence. It also produced an //academic research paper//, and is continuing to raise awareness for AI risks and mitigation strategies around the world. This month, we’re flying to Oxford again to run an Iteration Sprint which will condense everything we’ve learn in the past few months into an even leaner and simpler game!

Of course — a game isn’t really going to save the world from rogue AI, but more awareness and a way to explore different scenarios might! And since the game might be heading for a broader public release in the next year or so, we’ll be sharing more information as things progress.